Flexible packaging for sauce: how do we make it more sustainable?

Lorena Rodríguez, Packaging Researcher at AIMPLAS

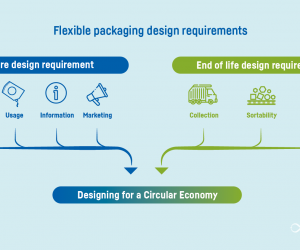

The main focus in the packaging sector currently lies in how to improve the environmental sustainability of packaging without affecting the quality and shelf life of the product it contains. This goal must consider a number of aspects such as eco-design packaging strategies, optimized use of resources (materials and energy), the transformation process and packaging shelf life (i.e. recyclability or recoverability). However, the plastic crisis has given rise to the belief that all packaging that is plastic free and instead contains paper or compostable plastic is sustainable. Consumers often believe that these materials are the only sustainable packaging solutions.

But are these packaging solutions really sustainable?

This article aims to examine current sustainable solutions for flexible sauce packaging, a type of product that presents recyclability challenges due to its purpose and dimensions. Additionally, it will also explain some terms commonly used to define end-of-life packaging such as recyclability, composability and biodegradability. The new Law 7/2022 on waste and contaminated soils for a circular economy , which was approved on 8 April, prohibits the use of plastic in the manufacture of single-use products and proposes a tax on non-reusable plastic packaging.

Flexible sauce containers are one of the most interesting but complex products, as they are often discarded after one use. However, they are not listed as banned products in the Single-Use Plastics (SUP) Directive or in Law 7/2022. Nevertheless, they are included in the list of plastic products that must be reduced in the coming years. For this reason, companies in the sector are working on solutions with reduced plastic for sauce packaging structures.

What happens to flexible sauce containers? Are they recycled? What will happen if the materials are changed?

When we make a change to a material, we often wonder if the change will actually make our packaging more sustainable. To answer this, it is necessary to understand what materials currently make up the packaging and how the packaging is dealt with at the end of its life to determine what alternatives are genuinely more sustainable.

How is flexible sauce packaging waste managed?

The first factor that determines the end of life of these containers is their size. Sauce containers, and containers in general, are usually bigger than 5 cm. This size does not present a problem at waste sorting plants. However, packaging that is smaller than 5 cm is classified as light fraction, which is usually made up of organic material, bottle caps and small containers, which are not recycled and end up as waste that is incinerated in the best-case scenario and buried in the worst-case scenario.

Therefore, it makes sense to seek an alternative end-of-life solution for these containers, since they are smaller than 5 cm and cannot be recycled by methods currently available at sorting plants. Biodegradable* or compostable** containers could present an alternative. However, material that does not pass through the trommel and would remain as light fraction waste, composed mainly of organic matter, would need to be treated to make compost.

It is important to take precautions when selecting alternative materials since data shows that not all compostable or biodegradable materials continue to be compostable or biodegradable after the printing and/or lamination process. They can lose their biodegradability or compostability due to the combination of materials, inks or adhesives. Therefore, it is always necessary to evaluate the end of life of the packaging we place on the market so that we can make verified statements about this possible end of life. It is important to remember that packaging can be labelled with the corresponding eco-label to indicate whether the product composts or biodegrades and under what conditions.

Particular attention should be paid to paper packaging, which is currently on the rise. Paper is a structural material and, as such, does not have any barrier properties to protect a product such as sauce. It therefore requires a plastic or polymer to provide it with barrier properties such as heat sealability. Moreover, it should be kept in mind that, even though sauce packaging is made mostly of paper, its high organic material content means it cannot be put in paper containers, since Spanish paper recyclers are currently unable to recycle this type of packaging.

Paper is a biodegradable material, and it would make sense for the final packaging product to be biodegradable. However, a polymer is needed to provide the product with barrier properties, so whether or not the final paper-based flexible packaging is biodegradable will depend on the polymer used. Another option would be to use a polymer that does not affect the biodegradability of the paper-based packaging. In both these cases, the commercially available solutions are very limited.

Therefore, the most suitable end of life for sauce packaging is currently the compostable option. The packaging can be disposed of in the brown container for organic waste, provided that the waste is processed at a composting plant. Compostable materials do not compost unless they are subjected to highly specific time and temperature conditions. If this is not the case, packaging waste disposed of in brown containers will end up as all other waste deposited in the yellow or blue containers.

How do I know whether my flexible sauce container is more sustainable?

This is not a simple question to answer. To respond with certainty, a life cycle assessment (LCA) of the packaging is necessary. This method is used to assess a product’s environmental impact in relation to aspects such as global warming, eutrophication and toxicity. Life cycle assessments take account of the product throughout its entire life, from procurement of the raw materials, through to the production and distribution stages and use of the packaging, right up until the end of its life.

Some marketing strategies that encourage the elimination of plastic promote the idea that a product is better for the environment simply because it contains less plastic. This can lead society to make quick, often incorrect, assumptions, because changing a packaging material without considering how that material will be managed at the end of its life is not always a more sustainable decision.

When deciding to change a material in a given packaging product, it is important to comply with national and European legislation, but objective sustainability methodologies such as LCAs are also necessary. This tool indicates the environmental impact of packaging in light of the production process, end of life and measures that can be taken to make it packaging more sustainable.

AIMPLAS has the technological capacity, knowledge and experience to propose and work on packaging solutions to improve the environmental sustainability of existing packaging. In addition, it also has the capacity to carry out exhaustive life cycle assessments on products to compare them with new sustainable packaging being developed. https://www.aimplas.net/

Definitions:

Biodegradable packaging*: packaging that can decompose into its constituent chemical elements due to the action of biological agents and different environmental conditions over a given period of time. This process will change the physical and chemical structure of the packaging until only the constituent elements (such as carbon or hydrogen) remain, which are then returned to the environment.

Compostable packaging**: packaging that decomposes under certain time and temperature conditions. When it disintegrates, it results in compost and does not leave any toxic residue in the environment.

Recyclable packaging***: packaging that can be transformed into new products or materials for later use. For a plastic packaging product to be considered recyclable, it must follow eco-design guidelines on packaging that can be recycled. These guidelines include information on the size of the packaging. Regardless of the material, products that are smaller than 5 cm cannot be separated in a sorting plant and, therefore, cannot be recycled.